(Posted on my earlier blog, but I want everything centralized, so here you go)

One of the major theological struggles of the past (and, arguably, still one today) is trying to reconcile belief in an all-powerful deity, with the existence of evil in the world. This problem, which has particularly plagued monotheists, is known as theodicy, and is going to be the main focus of this week's post, from a Traditional Stoic/polytheist perspective.

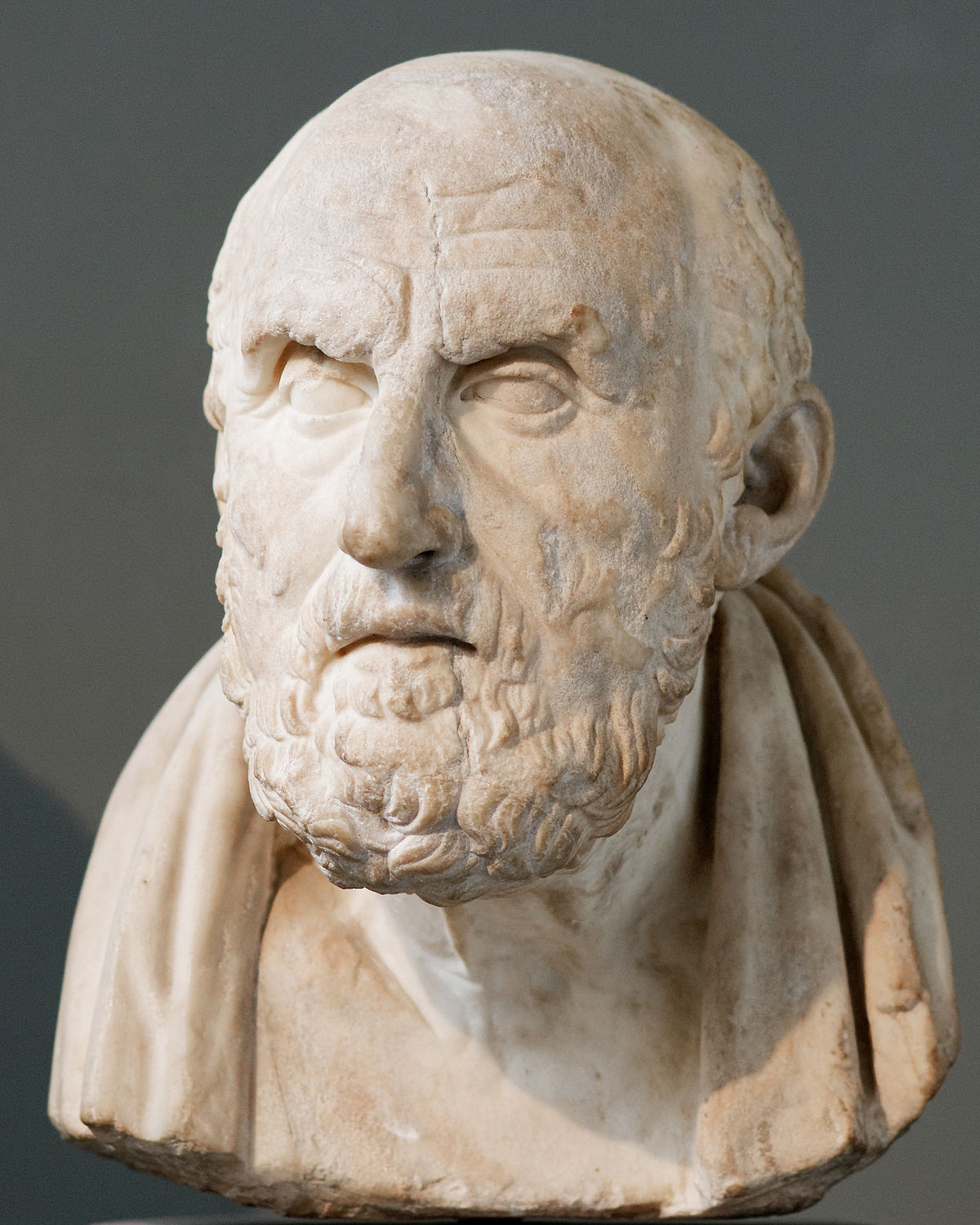

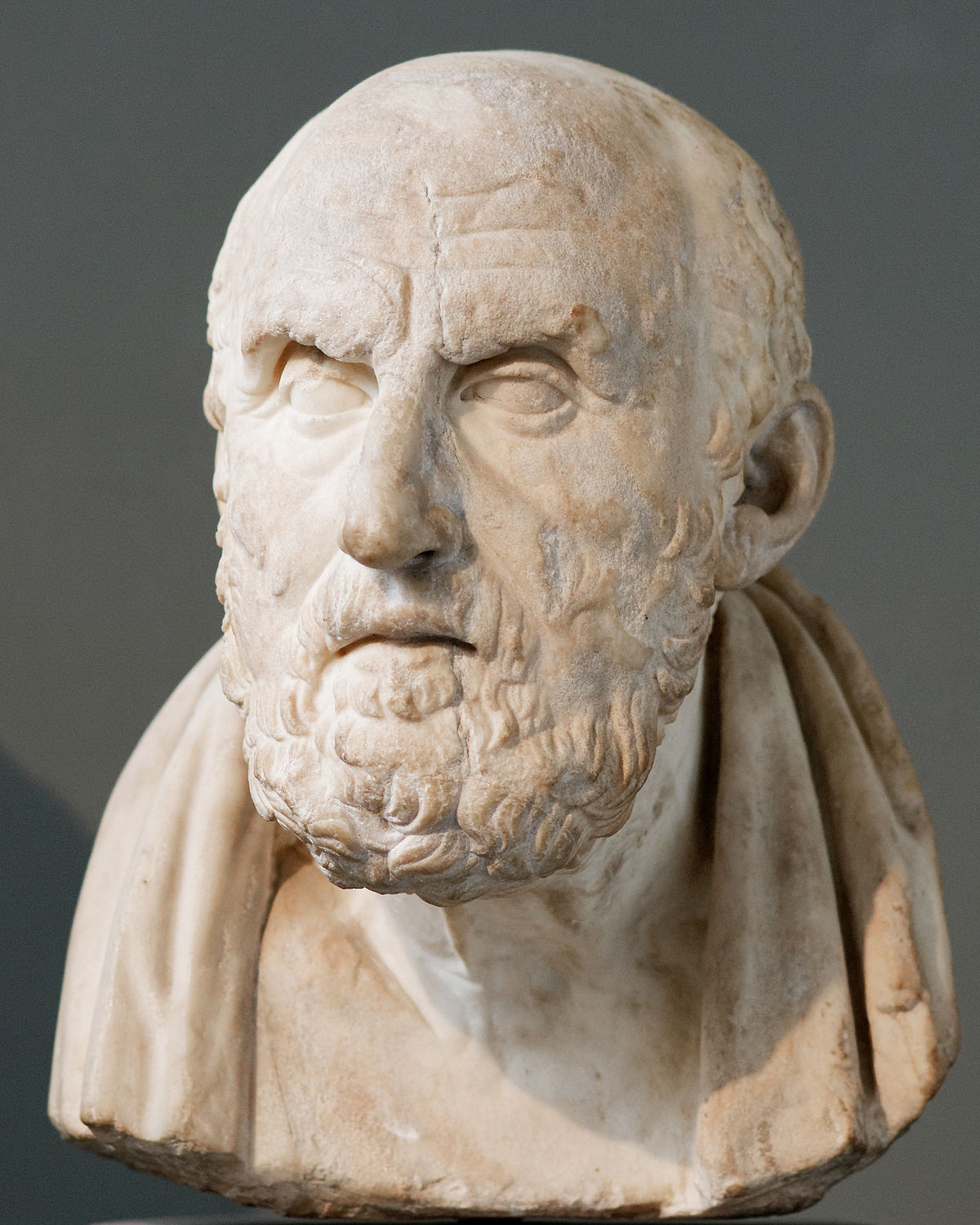

The Stoics were asked this question themselves. Chrysippus, the third head of the Stoa after Zeno and Cleanthes, was once asked how evil could exist in a good universe, to which he replied:

What, exactly, does this mean? Why should evil not be eradicated? Without evil, argued the Stoic, there can likewise be no good. Without injustice, justice could not exist, courage could not exist without cowardice, etc. Additionally,

- Chrysippus, as quoted by Plutarch, De Stoicorum Repugnantiis, 1051

But before we get too ahead off ourselves, we should probably begin by examining what is good, and what is evil. But even this is problematic, since our modern conception of evil does not exist in Stoicism. Rather, only the results of our personal choices/actions are good/evil; everything outside of our control, i.e., all external events, are neither good nor evil. All of the seemingly terrible things which befall people are, in actuality, neutral indifferents (adiaphora). They are indifferents because they are outside of our control. Furthermore, they are the product of a providential Cosmos (pronoia).

The only good things in life are virtue (specifically, courage, justice, wisdom, prudence), while the only bad things are vice (essentially a lack of virtue). Now, there are certain 'bad' things, but even then, it is not our modern sense of the word 'bad'. Rather, kakon refers to the opposite of virtue: stupidity, lack of self-restraint, injustice, cowardice. Therefore, Stoics deny that many of the seemingly bad things in the world are actually bad. First, because they are externals out of our control, and secondly, because death, sickness, poverty, etc., have nothing to do with virtue, and thirdly, because these are the events unfolding in our providential cosmos.

Now, when one is being tortured, it might be hard to say that one is not experiencing a terrible evil. However, the Stoic position is not meant to deny that these externals can be unpleasant, but rather that they are irrelevant to living a good life, which is the whole point of the philosophy. Seneca himself says that

- Seneca - On Providence

Note, that the misfortunes experienced are not evil, but rather "judging them to be bad and then struggling against what Nature has decreed will generate the sort of internal mental conflict that constitutes vice," and "the truly virtuous will always welcome adversity", since "disaster is the occasion for virtue." (Sellars, The Stoics on Evil)

Now, this is all good to say if one has never experiences any personal hardship. This is precisely why Seneca says that we must train ourselves for when Fortuna tests us next:

- Seneca - On Providence

John Sellars asks in his commentary on this passage:

-Plutarch, Stoic Self-Contradictions, 1035C-D

Everything which occurs is the result of divine providence, which is fate (The Goddess Heimarmene (Εἱμαρμένη), who orders the fate of the Universe as a whole, rather than the destinies of individuals.) The fourth-century philosopher Calcidius quoted Chrysippus as saying:

But Chrysippus did think about this issue deeply, suggesting that

– John Sellars, The Stoics on Evil

But, this can be explained by the limitations to divine providence re: omniscience and omnipotence. Specifically, that the Gods are not all-powerful, nor all-knowing, powerful and great as they are.

Now that we have seen (very brief) explanation of the Stoics on evil, what about polytheism? The Gods are not omnipotent and omniscient, powerful though they may be. The argument from evil is a significant challenge to monotheists, yet it offers little challenge to other belief systems. If a God is not omniscient/omnipotent, suffering may be explained by the God’s limitation.

From John Michael Greer (who now posts here at ecosophia; go check him out!), who is worth quoting at length:

Greer then brings up second century Christian thinker Irenaeus, who argued that the Christian God permits suffering because such evil allows mankind to “develop spiritually and morally.” Now, on the surface, this might seem rather similar to what Seneca was saying earlier, since, Irenaeus says, without evil and suffering, mankind cannot develop the virtues of courage, etc. But, as Greer notes, since Irenaeus is working within the monotheist worldview,

I can go on and on quoting Greer on theodicy, but I’ll leave you with the following, again from Greer:

Throughout this post, I have made oblique reference to the polytheism of Ancient Greece, which permeated its philosophical schools, including the Ancient Stoa. While the majority of modern practitioners of stoicism may be the New Atheists, that certainly was not the case two millennia ago. But even Traditional Stoics ascribe to the notion of a Cosmic God (what is often referred to by Epictetus et al., as Zeus), and (falsely, I believe) charges of monotheism have been leveled against the ancient school. Much like the argument that Epicureans were atheists (they were not), this notion doesn’t seem to hold much water. Very soon, I will be posting about the polytheism of the ancient Stoics.

For more information, see:

The Stoic Concept of Evil, by A. A. Long,

The Stoics on Evil, by John Sellars.

A World Full of Gods: An Inquiry into Polytheism, by John Michael Greer.

One of the major theological struggles of the past (and, arguably, still one today) is trying to reconcile belief in an all-powerful deity, with the existence of evil in the world. This problem, which has particularly plagued monotheists, is known as theodicy, and is going to be the main focus of this week's post, from a Traditional Stoic/polytheist perspective.

The Stoics were asked this question themselves. Chrysippus, the third head of the Stoa after Zeno and Cleanthes, was once asked how evil could exist in a good universe, to which he replied:

Evil cannot be removed, nor is it well that it should be removed.

What, exactly, does this mean? Why should evil not be eradicated? Without evil, argued the Stoic, there can likewise be no good. Without injustice, justice could not exist, courage could not exist without cowardice, etc. Additionally,

Evils are distributed according to the rational will of Zeus, either to punish the wicked or because they are important to the world-order as a whole. Thus evil is good under disguise, and is ultimately conducive to the best.

- Chrysippus, as quoted by Plutarch, De Stoicorum Repugnantiis, 1051

But before we get too ahead off ourselves, we should probably begin by examining what is good, and what is evil. But even this is problematic, since our modern conception of evil does not exist in Stoicism. Rather, only the results of our personal choices/actions are good/evil; everything outside of our control, i.e., all external events, are neither good nor evil. All of the seemingly terrible things which befall people are, in actuality, neutral indifferents (adiaphora). They are indifferents because they are outside of our control. Furthermore, they are the product of a providential Cosmos (pronoia).

The only good things in life are virtue (specifically, courage, justice, wisdom, prudence), while the only bad things are vice (essentially a lack of virtue). Now, there are certain 'bad' things, but even then, it is not our modern sense of the word 'bad'. Rather, kakon refers to the opposite of virtue: stupidity, lack of self-restraint, injustice, cowardice. Therefore, Stoics deny that many of the seemingly bad things in the world are actually bad. First, because they are externals out of our control, and secondly, because death, sickness, poverty, etc., have nothing to do with virtue, and thirdly, because these are the events unfolding in our providential cosmos.

Now, when one is being tortured, it might be hard to say that one is not experiencing a terrible evil. However, the Stoic position is not meant to deny that these externals can be unpleasant, but rather that they are irrelevant to living a good life, which is the whole point of the philosophy. Seneca himself says that

nothing bad can happen to a good man, since no external thing is either good or bad. Also, using Seneca as an example, the Cosmos (Zeus) is a deity which is a tough, albeit loving father, who sets challenges in our way to test our strength.

I shall show how true evils are not those which appear to be so: I now make this point, that the things you call hardships, that you call adversities and detestable, are actually of benefit, first to the very person it happens to, and secondly to the whole human race, which matters more to the Gods than individuals do [... because we find out who we are truly only when we are put to test by events...]

- Seneca - On Providence

Note, that the misfortunes experienced are not evil, but rather "judging them to be bad and then struggling against what Nature has decreed will generate the sort of internal mental conflict that constitutes vice," and "the truly virtuous will always welcome adversity", since "disaster is the occasion for virtue." (Sellars, The Stoics on Evil)

Now, this is all good to say if one has never experiences any personal hardship. This is precisely why Seneca says that we must train ourselves for when Fortuna tests us next:

How do I know how calmly you will bear the loss of children, if you see all the ones you have fathered? I have heard you giving consolation to others: that was when I might have seen your true worth, had you been consoling yourself, or telling yourself not to grieve.

- Seneca - On Providence

John Sellars asks in his commentary on this passage:

How can anyone know how well they would bear the loss of a loved one until they go through with it?The Stoics have always linked their ethics to their theology. Chrysippus wrote extensively on Stoic physics. Sadly, most of his writings are lost, and we must rely on secondary and tertiary sources. Greco-Roman historian and Priest to Apollo at Delphi, Plutarch wrote that Chrysippus held that theology goes ahead of ethics:

For there is no other or more suitable way of approaching the theory of good and evil or the virtues or happiness then from the universal nature and from the dispensation of the universe… For the theory of good and evil must be connected with these, since good and evil have no better beginning or point of reference and physical speculation is to be undertaken for no other purpose than for the discrimination of good and evil.

-Plutarch, Stoic Self-Contradictions, 1035C-D

Everything which occurs is the result of divine providence, which is fate (The Goddess Heimarmene (Εἱμαρμένη), who orders the fate of the Universe as a whole, rather than the destinies of individuals.) The fourth-century philosopher Calcidius quoted Chrysippus as saying:

For providence will be God’s will, and furthermore His will is the series of causes. In virtue of being his will, it is providence. In virtue of also being the series of causes it gets the additional name “fate”. Consequently everything in accordance with fate is also the product of providence, and likewise everything in accordance with providence is the product of fate.

But Chrysippus did think about this issue deeply, suggesting that

In some cases providence inadvertently neglects some details when aiming for the general good.

– John Sellars, The Stoics on Evil

But, this can be explained by the limitations to divine providence re: omniscience and omnipotence. Specifically, that the Gods are not all-powerful, nor all-knowing, powerful and great as they are.

Now that we have seen (very brief) explanation of the Stoics on evil, what about polytheism? The Gods are not omnipotent and omniscient, powerful though they may be. The argument from evil is a significant challenge to monotheists, yet it offers little challenge to other belief systems. If a God is not omniscient/omnipotent, suffering may be explained by the God’s limitation.

From John Michael Greer (who now posts here at ecosophia; go check him out!), who is worth quoting at length:

Christian philosopher Augustine of Hippo argues that suffering is caused by the misuse of free will by created beings, not by divine actions. Human evils such as murder and rape are the product of free human choice, while natural evils such as earthquakes and plagues are either the product of free choices by nonhuman beings such as devils, or punishment for human sin. Thus the evils in the world are not the God’s fault.

This theodicy, as Friedrich Sheleiermacher pointed out in the early nineteenth century, is an evasion of divine responsibility. An omniscient, omnipotent, and omnibenevolent God who created the universe would have known in advance exactly what evils would follow, and could have adjusted the details of creation to prevent many of them.

Greer then brings up second century Christian thinker Irenaeus, who argued that the Christian God permits suffering because such evil allows mankind to “develop spiritually and morally.” Now, on the surface, this might seem rather similar to what Seneca was saying earlier, since, Irenaeus says, without evil and suffering, mankind cannot develop the virtues of courage, etc. But, as Greer notes, since Irenaeus is working within the monotheist worldview,

The problem with his defense is that it conflicts with the claim of divine omnipotence. […] Some defenders of this theodicy have claimed that the only alternative to the world we see is a “playground paradise”in which weapons and poisons do no harm[…] Yet if a God is omnipotent, he has many more choices than these.

Consider the case of childhood cancer. An omnipotent God could just as well have created human bodies so that cancer in children did not cause excruciating pain. In such a world, parents of dying children would still have to confront the reality of transience, loss, grief, and their own mortality; on the other hand, there would be a good deal less pointless misery in the world. […]

Again, if divine omnipotence means anything, it means that the words “has to” do not apply to the God in question at all.

I can go on and on quoting Greer on theodicy, but I’ll leave you with the following, again from Greer:

If a God is not omnibenevolent, suffering may be explained by the fact that the God may have no motive to eliminate them.

If more than one God exists, and if conflict between Gods is possible, then the argument from evil loses nearly all of its force, since the benevolent action of one God could be countered by the opposing action of another.

Since the many Gods of traditional polytheism are limited in power and knowledge, and are associated with specific moral ideas and qualities (rather than goodness in general), the existence of evil and unnecessary suffering in a polytheist universe causes no logical difficulty. Indeed, the absence of evil and unnecessary suffering in such a universe would be a good deal more surprising.

Throughout this post, I have made oblique reference to the polytheism of Ancient Greece, which permeated its philosophical schools, including the Ancient Stoa. While the majority of modern practitioners of stoicism may be the New Atheists, that certainly was not the case two millennia ago. But even Traditional Stoics ascribe to the notion of a Cosmic God (what is often referred to by Epictetus et al., as Zeus), and (falsely, I believe) charges of monotheism have been leveled against the ancient school. Much like the argument that Epicureans were atheists (they were not), this notion doesn’t seem to hold much water. Very soon, I will be posting about the polytheism of the ancient Stoics.

For more information, see:

The Stoic Concept of Evil, by A. A. Long,

The Stoics on Evil, by John Sellars.

A World Full of Gods: An Inquiry into Polytheism, by John Michael Greer.